Table of Contents

Executive Summary

As the one-year anniversary of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) approached, We the Doers, a new organization of reform-minded former civil servants, convened a panel to answer a single question: “What would it actually take to deliver the federal government the American people deserve – in an efficient, cost-effective manner?”

This group’s recommendations, drawn from a combined 88 years of federal leadership experience and described in detail in this report, were far-reaching and innovative:

- Focus on results that the average American values and can understand across three categories: delivering outcomes, enhancing customer service, and maximizing taxpayers’ return on investment

- Align performance measurement, reporting, and operational priorities with these results

- Build a feedback loop between civil servants and Congress

- Limit the length of bills, either by statute or House and Senate procedures, while increasing the amount of time members have to review and consult with constituents, policy experts, and the civil servants who would implement these bills

- Focus agency legislation on broad policy intent language, and a requirement for the agency to propose a concise, measurable implementation framework consistent with this intent within a reasonable prescribed timeframe.

- Create a separate mechanism for rank-and-file civil servants to raise concerns about unintended consequences of a proposed bill, hidden costs, and potential implementation challenges directly to Congressional oversight committees, without attribution or filtering by agency political staff

- Fix the broken budget process

- End disruptive government shutdowns

- Shift to two-year funding to better align budget and procurement cycles and allow Congress to allocate more time for a productive two-way dialogue with civil servants about how to improve results and federal service delivery

- Incentivize savings and reduce wasteful year-end spending by allowing agencies to automatically retain 50 percent of unexpended funds at the end of each budget cycle for future-year use to fund agency priorities

- Re-imagine the governance processes used to allocate appropriated funding, particularly around technology products, to focus on results and return on investment

- Build a culture that focuses on delivery

- Streamline the rules, and empower managers to hire the right people and correct or remove underperformers while still respecting due process

- Make government a savvy customer

- Attract and reward courageous leadership

- Become competent at in-house technical delivery

Reflecting on the Legacy of DOGE

It has been one year since the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) took a chainsaw to the federal bureaucracy. The central premise of DOGE was that reducing the federal workforce was synonymous with efficiency. By that standard, DOGE succeeded.

But for those of us who subscribe to Merriam-Webster’s definition of efficiency (“capable of producing desired results without wasting materials, time, or energy”) the picture is much less rosy. Wait times reportedly skyrocketed at the Social Security Administration. One year after the devastation of Hurricane Helene, not a single homeowner had received relief under FEMA’s Congressionally-authorized Hazard Mitigation Program. Experts in charge of safeguarding the nation’s nuclear stockpile were hastily fired and then rehired. And after all that, federal spending increased by $154 billion between 2024 and 2025.

As professionals with a combined 88 years of federal government experience across nine Federal agencies1, we are disappointed but not surprised. DOGE treated the government like a startup to be disrupted, rather than a complex operating system bound by law, incentives, culture, and accountability structures. But we know you can’t fix a system this complex with bravado, by inserting a cadre of engineers, or by chasing “quick wins.” You also can’t fix it with the academic, incremental approach that has been attempted by previous administrations. You fix it by understanding how power, process, and delivery actually work, and then changing the rules of the game to make it winnable.

What the Civil Servants of We the Doers Know

We know a real reform agenda must be citizen-led because any durable, successful reform needs broad-based and sustained Congressional support – and obtaining Congressional support can only happen when the people exert pressure on their elected representatives. Congress shapes the contours of the public debate over the size and scope of government, dictates which programs get funded, and passes agency oversight legislation – nearly always well-intended – which too often results in a tangle of red tape that impedes the timely and cost-effective fulfillment of the agency’s mission. Members of Congress should have a vested interest in the success of any government reform initiatives, because “government of the people, by the people, and for the people” cannot long endure unless the people see that it can deliver.

We know real reform must also be civil servant-informed because we have the necessary insight about why the federal government is broken and how to fix it. We were focused on improving effectiveness and efficiency in our agencies long before DOGE arrived and, despite obstacles both large and small, we have the track record to prove it. Plus, we have credibility as nonpartisan experts who have worked in both Democratic and Republican administrations. Rather than sidelining or even “traumatizing” civil servants, any effort at sustainable reform must engage civil servants as partners in identifying and implementing solutions to reduce costs, turbocharge efficiency, and drive value.

Some may discount civil servants’ ability to spearhead the necessary reforms, reasonably asking why we should trust civil servants when they have previously been unable to deliver a government that efficiently and effectively delivers on its promises. But this objection fails to recognize the extent to which civil servants have historically been constrained by the bureaucracies in which they must operate. Our ability to deliver has been limited by our narrowly defined roles, political leadership, a risk-averse government culture, and an ever-growing tangle of federal regulations, Congressional directives, and executive orders that led to a culture that prioritizes checking boxes at the expense of driving results.

Why We Wrote This Report

Now that we are no longer federal officials, we are free to speak truth to power and advocate for lasting change that cuts across agencies.

That’s why on December 12, 2025, We the Doers convened a panel of seven former senior-level civil servants, with a combined 88 years of experience across nine federal agencies, who drew on their diverse experiences to attempt to answer a single question:

“What would it actually take to deliver the federal government the American people deserve – in an efficient, cost-effective manner?”

Or in other words, what would we have changed if we had the power entrusted to DOGE but defined efficiency in terms of effectively delivering value? To us, that means building a government that provides:

- the services the American people desire, as determined by their elected representatives and financed through the appropriations process,

- customer-friendly experiences that delivers those services how, when, and where American citizens want them, in the least burdensome manner possible; and

- maximum return on the taxpayers’ investment.

Our conversation was as wide-ranging as our diverse experiences and backgrounds, but we managed to distill our insights into the four root causes below and provide a menu of possible solutions for each.

We recognize that these initial solution proposals will need further refinement as others join the conversation and point out flaws in our approach or areas for improvement. We also recognize that many of our ideas are not new. Several of the proposed approaches have been written about or discussed in previous government reform conversations but were never able to be implemented. Yet we share the full scope of our first round of ideas today because we think it is important to start a dialogue with the American public and their elected representatives about what real, lasting reform could look like in a post-DOGE world.

And because we think it is important to put former civil servants – “the doers” – back at the center of the conversation.

Our Goal: An Effective, Efficient, Trustworthy Government that Delivers Value

Surveys show that most Americans do not trust the federal government, are increasingly concerned about the cost of running today’s government (i.e. the national debt), and believe today’s federal government is corrupt and wasteful.2 When Americans do seek services from the federal government, they are dissatisfied with their experience.

As former civil servants, we empathize and we agree. All too often, the federal government fails to provide value to citizens because it is dysfunctional.

In order to build a government that functions (one that can be used effectively to achieve the goals of any administration of representatives duly elected through the democratic process), we must first define what a functional government looks like.

Pillars of Functional Government

Every actionable plan starts with clear goals and desired results. What do we hope and expect the federal government of the world’s greatest democratic experiment to become? The functional, value-delivering government we envision is objectively, measurably:

- Effective

- Outcome-driven. It does what it says it’s going to do and delivers results that matter to the average American. It communicates those results in a way the average American can easily access and understand.

- Customer-oriented. It’s intuitive, easy and pleasant (maybe even delightful!) to directly interact with the government as an individual, small business, corporation, grantee, or local or state government. And it’s easy for federal agencies to get what they need from sister agencies (e.g., outsourced services, data, or technical assistance).

- Efficient

- Cost-effective. The government maximizes taxpayers’ return on investments, delivering the most bang for the buck. No taxpayer dollars are wasted.

- Unified. Bureaucratic complexities are the government’s problem, not the people’s problem. A single point of entry into the federal government, with a single point of contact, is the only thing an average American will see or interact with even if their need requires action from multiple federal agencies.

- Proactive. If one part of the government requires information from another part of the government to meet a citizen’s need, it will proactively get and use that information on behalf of the citizen.

- Timely. It works as fast as needed for a given situation. Emergencies are resolved within hours or days. Regulatory oversight needs are resolved within weeks or months. Nothing in a functional government takes years.

- Concise. Plain language is important, but significantly less language is also necessary on every form, letter, website, and publication.

- Trustworthy

- Ethical. The people who make up the government act with integrity and ethics.

- Reliable. The services delivered are consistent, reliable, and fair. Americans can rely on the accuracy of data and information from government sources.

- Competent. The people who make up the government know how to do their jobs, perform those jobs well, and understand how their jobs fit into the bigger picture of service delivery.

- Right-sized. The size of an agency or office’s workforce (as well as its contractor support) is determined by the size, scope, and complexity of its mission – not by arbitrary targets set by an external body unfamiliar with its work. Some areas will shrink while others may grow, though we expect the overall size of the workforce to reduce as smart, strategic cuts are made.

Why the Federal Government Isn’t Functional Today, and How to Fix It

The good news is that we identified just four primary root causes of government dysfunction. The bad news is that each of the four primary root causes is decades (or more) in the making, extraordinarily complex and interconnected, and carefully protected by an overlapping tangle of laws, executive orders, regulations, and culture.

The problems are all solvable, but the work of solving them will be both hard and decidedly unglamorous. It requires sustained attention to detail at every level of the bureaucracy, long after the press releases become old news and the political attention shifts. And the systems are woven together so tightly that solving only one root cause will be largely ineffective – like pulling up all the weeds in a garden but leaving their seeds to grow next season. We must solve all four to succeed.

Root Cause 1: The Bottom Line is Undefined

Why It’s a Problem: Current Performance Data Doesn’t Drive Meaningful Results

In a private sector company, measuring success is easy. The bottom line is shareholder value in terms of net profit (revenue minus expenses). A thousand different strategies and investments and reorganizations and acquisitions and other leadership decisions will be made during any CEO’s tenure, but they are all in service of the financial bottom line. If the CEO can deliver value for shareholders, he or she is considered successful.

Government agencies have not had the luxury of such clarity.

The Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA), its update in 2010, and several other pieces of “accountability” legislation, were valiant attempts to force agencies to measure and report meaningful results. Some of our agencies use this process fairly well. The U.S. Economic Development Administration, for example, reports jobs and private investment for every grant, and aggregates this information into a portfolio-level view of its economic development impact.

Unfortunately, over time the GPRA process has devolved into a bewildering, uncoordinated profusion of metrics, siloed by program, and not validated by a uniform methodology that is understood or valued by the American public. (You can view examples of agency performance reports on Performance.gov and judge for yourself how meaningfully they represent outcomes of interest to the American public. Also note that, in theory, the measured results are supposed to flow from the President’s Management Agenda.)

These metrics are often created solely for the purpose of satisfying GPRA, almost as an afterthought, and are therefore divorced from the strategic planning process. Many times, the GPRA-mandated metrics are created by a program manager, who may not have an overall view of agency priorities, in isolation from other similar programs at the same agency.

And even when the metrics are meaningful, there is no consequence for failing to meet performance targets. The agency simply includes an explanation of why it failed to meet the target in its agency performance report.

Overall, the GPRA process has become yet another exercise that civil servants slog through to produce paperwork that few members of Congress, let alone the public, ever read. If they do read these reports, they are left wondering whether the data collected is accurate, whether it matters, and whether anyone is actually learning from trends in the data and leveraging this learning to drive improvement in outcomes. Perhaps most importantly, since agencies report separately using separate methodology, there is no way to get a sense of how our government is delivering against key priorities in the aggregate, or how different programs with similar missions compare against each other.

Without this information, it’s hard for Congress or voters to know which programs most cost-effectively deliver desired results, which in turn makes it hard to decide which programs should be expanded and which should sunset.

We believe some of this problem of meaningless metrics is unintentional – the product of a culture that focuses on “checking the box” on GPRA rather than honoring its true intent, and on measuring what is easy to measure rather than what is important – while some of it is by design.

Many programs, particularly smaller ones, were created by Congress to serve a particular constituency or advocacy group. In these cases, it is considered desirable to show that the member of Congress is getting funds to a good cause, whether or not those funds move the needle on real-world results. In these cases, measuring outcomes rather than activity might shed an unflattering light on the program, which could result in staffing and funding cuts. To maintain funding to the program that pays their salaries, the people responsible for developing performance measurement are incentivized to select the metrics that would be least damaging to report.

Solution: Define the Bottom Line – Everything Else is Noise

Focusing on results that the average American values and can understand is foundational to every other reform. While most of our other recommendations focus on efficiency in the provision of government services, this one speaks to the quality and utility of services provided: the return on taxpayers’ investment.

Start Measuring What Matters

What gets measured gets done.

We the Doers advocates for a whole new bottom-line model for federal agencies, based on what the American public wants its government to achieve. “What gets measured gets done” may be a truism, but we have found it to be accurate. If the government had to measure citizen-defined outcomes in a consistent, verifiable manner, it would drive accountability to improve these outcomes and allow Congress to make meaningful, citizen-informed decisions about which programs to expand, which programs to cut, and which to combine.

We envision that this model would:

- Be intuitive, citizen-led, and measure success against three dimensions: achievement of citizen-desired policy outcomes/results, customer experience, and cost-effectiveness (return on taxpayer investment). These metrics would then become the basis for a federal government-wide dashboard that would replace the current system of voluminous agency-specific reports.

- Policy outcome/results metrics. Involve citizens in a process of developing concrete, easy-to-understand metrics to measure results against broad policy goals important to voters (i.e. create high-paying jobs, ensure the mail arrives on time, reduce cancer rates), without reference to specific agencies or programs. For example, if citizens identified training Americans for high-paying, high-growth occupations as a goal, all federal workforce development programs might be required to track and report job placement rates in target industries, increases in earnings, return on investment (graduates placed per taxpayer dollar invested), and customer service satisfaction (trainee satisfaction and employer satisfaction).

- Customer experience (CX) metrics. Involve citizens in a process of developing cross-cutting metrics for customer experience to complement the policy outcome/results metrics. These CX metrics will require agencies to track, in a standardized way, how they provide services and whether their customers – the American public – are satisfied with their experience. Continuously monitoring these metrics, and incorporating them into accountability structures, will incentivize federal agencies to focus on providing services in a user-friendly, minimally burdensome manner.

- Cost-effectiveness/return on investment metrics. Use the citizen-led policy outcome/results metrics to consistently measure the results achieved per dollar of taxpayer investment. This will allow American voters and Congress to directly compare programs with similar objectives and determine which are the most cost-efficient (and therefore should perhaps be expanded) and which are the least efficient. For example, Congress might wish to expand a job creation program with a cost per job created of $5,000, while cutting a program with a cost per job of $15,000.

- Create multiple levels of data transparency. Align these government-wide metrics to individual institutions and programs and require agencies to measure their programs against the standardized metrics using a uniform methodology. Publicly document the methodology and provide all raw source data for public use, to allow for academic and media scrutiny to the extent allowable by law.

- Be appropriately resourced. Provide adequate funding, qualified staff with the necessary quantitative skills, software and IT platforms for appropriate data science work, and any other resources necessary for agency data collection and analysis, as well as an independent body to test and verify a sample of agency data to ensure consistent data quality.

Performance Data Can Be Easy to Collect—and Can Meaningfully Inform Congressional Decisions

A Case Study from the State Small Business Credit Initiative

When We the Doers co-founder Maureen Klovers began working for the U.S. Department of Treasury’s brand-new $1.5 billion State Small Business Credit Initiative (SSBCI), she immediately saw a need to create a user-friendly data reporting system that would allow Treasury to monitor grantees’ compliance with statutory requirements and measure individual grantees’ performance and aggregate program performance against Congress’s objective: turbocharging and de-risking private lending and venture capital investments to create and retain jobs in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

She worked with state government grantees to develop requirements for a system that seamlessly integrated with their existing loan software and worked with a contractor to ensure the development and on-time, on-budget launch of the system in just four months.

In 2016, as the program wound down as scheduled, Treasury commissioned a third-party evaluation of the program, which leveraged the program’s performance data (admittedly, self-reported by grantees since Treasury did not have the funding to independently verify the data) to determine that the program ultimately expended $1.04 billion, spurred $8 in private investment for every $1 of public investment and created or retained over 190,000 jobs, with 42 percent of small businesses supported located in low- and moderate-income communities.

Voters can argue whether $5,474 of taxpayer money spent per job created or retained was a good investment, but at least they have the information to do so.

Congress evidently determined that this program model yielded a good “bang for the buck.” In 2021, it appropriated $10 billion for another round of SSBCI funding, as part of the American Rescue Act.

Stop Measuring the Wrong Things – So They Won’t Get Done, By Design

The corollary to “what gets measured gets done” is that what doesn’t get measured doesn’t get done – or, at least, is de-emphasized.

One of the most common statements during our initial We the Doers workshop was “when everything is a priority, nothing is a priority.” Despite serving in leadership positions, we felt that an inordinate amount of our time as civil servants was spent navigating our way through (and sometimes around) a bewildering plethora of statutes and regulations. Most were well-intentioned to accomplish some public purpose. Examples include employing more veterans and individuals with disabilities, promoting small and disadvantaged businesses, or preventing a recurrence of some instance of fraud that occurred in the distant past. But the rules and processes designed to achieve these goals were often peripheral to the mission, and in many cases actively hindered mission fulfillment.

Having a much smaller, more heavily curated list of meaningful, citizen-informed outcome metrics would focus minds and resources. Funding would flow to activities that drove improvement in those outcomes, and away from activities that were peripheral or detracted from those outcomes.

And when there was a tradeoff decision to be made between driving improvement in those outcomes and achieving some other purpose, it would drive a meaningful, data-informed conversation about whether we were willing to accept this tradeoff, and at what cost.

We envision that the reduction of unhelpful metrics, rules, and processes would:

- Start with a blank slate. There are two ways to approach a transformative rewrite of any part of a bureaucracy: either start with the full scope of existing metrics, rules, laws, processes, and regulations and argue about which ones to cut, or start with a blank slate of no metrics, rules, law processes, and regulations and argue about which ones to add back in or create from scratch. This metrics-reduction effort will be better served by using the blank-slate approach. By default, all existing agency and cross-government metrics would be assumed to be deleted (in theory, if not yet in practice), and decisions about what to reintroduce would be based on the framework of the citizen-led outcome objectives described above. This places the burden of proof on those arguing for keeping existing metrics or creating new ones, rather than those arguing for deletion. Of course, modifying laws and regulations is not a trivial task, so some parts of the new outcome measurement framework would take effect only after enactment of appropriate legislative and regulatory adjustments. The order of operations is critical here. A re-imagining of GPRA, Office of Personnel Management (OPM) reporting policies, Paperwork Reduction Act, and other red tape that currently stands in the way of a government measurement overhaul must be guided by a clear, specific vision of what changes to those items are intended to achieve. A blank-slate framework development process will be the cleanest and most effective way to set that vision.

- Be human led with AI in the loop. Much has been written this year about generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) and the potential for GenAI to use large language models (LLMs) like those powering ChatGPT and Google Gemini to identify bureaucratic overreach and suggest reductions in red tape3. But these technologies are only as good as their data inputs, and the data inputs of the current bureaucracy are impossibly self-conflicting and irreconcilably messy. Humans who have dealt with the current state are still best positioned to intuitively to ignore the noise in the existing documentation, understand what does and does not make sense to keep, and may be more likely to make broader cuts than a language model that is considering millions of pages of text describing rules that are already functionally obsolete. However, these models may be useful as a cross-check of the human-defined change recommendations against the full scope of existing bureaucracy, and to surface information that may exist in the human team’s blind spots.

Root Cause 2: No Feedback Loop with Congress

Much of the discussion at our first We the Doers workshop centered on one inconvenient truth: the dysfunction in the executive branch is a mirror image of the dysfunction in Congress.

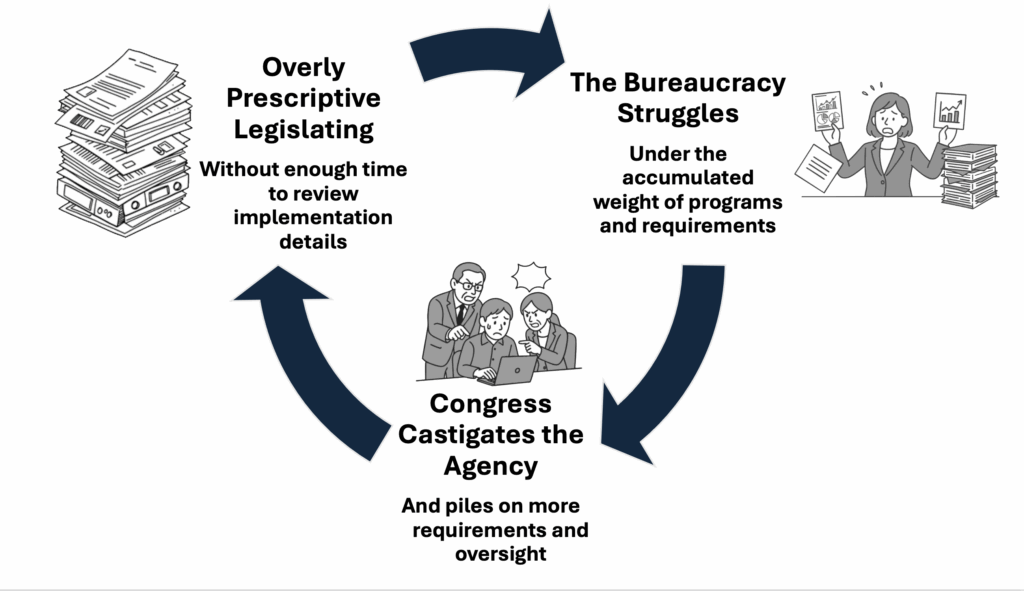

As detailed below, this vicious cycle begins with Congress’s overly prescriptive legislating, which then causes agencies to struggle to respond, and results in Congress reprimanding the agencies and adding more requirements and oversight.

Why It’s a Problem: The Vicious Cycle

Phase 1: Overly Prescriptive Legislation

The dysfunction first manifests itself in voluminous legislation that members of Congress could not possibly have the time to understand, or even read, prior to a vote.

Often, draft legislation exceeding a thousand pages is released just hours before a member must vote on it. Even the most diligent member of Congress therefore does not have the time to consult with the civil servants who would actually have to implement the legislation about the resources or timeline needed for successful implementation, whether a new program would fit better in another agency, or whether a new requirement could have unintended consequences that would hamper other Congressional priorities. Nor does this member have the time to educate and consult his or her constituents about any resulting changes in federal program delivery or evaluate the trade-off of any increased burden on program beneficiaries or grantees.

Many times, the new legislation creates new programs very similar to existing programs, but with slightly tweaked eligibility requirements to benefit a particular constituency. These new programs may be in completely different agencies from the ones who traditionally manage these programs, and the agencies receiving these new programs often lack the staff, contractors, implementing regulations, and infrastructure (IT systems, facilities, etc.) to implement the new program. As just one example, witness the plethora of small business lending programs, all with different eligibility requirements, across the Small Business Administration, Treasury, USDA Rural Development, U.S. Economic Development Administration (part of the Department of Commerce).

In other cases, the new legislation creates sweeping new requirements that serve the needs of a particular constituency or an important public purpose but create an unfunded mandate4 – and often new red tape – that agencies struggle to implement. As an example, see the case study below on the Build America, Buy America Act’s unfunded mandate.

Case Study: The Unfunded Mandate of the Build America, Buy America Act

The Build America, Buy America Act (BABAA) is a classic example of unfunded mandate spurred by the understandable desire of many Americans to support the American construction supplies industry and, by extension, American manufacturing jobs.

The Act requires that “none of the funds made available for a Federal financial assistance program for infrastructure, including each deficient program, may be obligated for a project unless all of the iron, steel, manufactured products, and construction materials used in the project are produced in the United States.”

Agencies are permitted to waive the application of the BABAA requirements based on public interest, nonavailability of domestically produced products, or when total construction costs with domestically produced products would be more than 25 percent greater than with foreign-sourced products.

The Act did not provide any additional funding for agencies overseeing grant-funded construction projects to undertake the following necessary actions:

- Develop detailed waiver policies and procedures,

- Upgrade IT systems to allow for the electronic submission and processing of waivers,

- Hire staff or contractors with experience in the construction industry to:

- Review waivers and ensure the company/recipient/subrecipient has done any due diligence (and hasn’t, for example, overlooked any domestic suppliers),

- Complete the required complex public comment process,

- Conduct monitoring and site visits of all projects claiming to be compliant with BABAA to ensure the products used are compliant.

As a result, to comply with this unfunded mandate, agencies had to pull IT dollars and legal, program, and engineering staff from mission-critical projects.

The paperwork burden on construction contractors, grantees, and subrecipients also skyrocketed, and the cost of construction projects increased, meaning that individual projects could fund fewer infrastructure projects overall.

Only the voters and their elected representatives can decide if the impact on American manufacturing jobs justifies the increased cost and burden. It is the job of civil servants to faithfully execute this law and others to the best of our ability. But we think it’s critical to have a two-way dialogue up front about the tradeoffs involved in such mandates–and how to provide adequate resources for successful implementation.

Phase 2: The Bureaucracy Struggles Under the Accumulated Weight of Programs and Requirements

As Congress continues to add more programs and requirements without ever seeming to take any away, and the President piles on with more executive orders, the bureaucracy strains to the breaking point.

Because Congress and the executive branch have made procurement and hiring policies incredibly unwieldy, program staff are unable to:

- quickly bring on board the temporary staff and/or contractors to draft the necessary new regulations and shepherd them through the lengthy public comment process;

- develop new policies, procedures, and forms to reflect the new requirements;

- educate eligible recipients about the program changes; and

- upgrade or build the necessary technical infrastructure to deliver the program requirements.

Information technology systems – which are never cutting edge to start with – become an ungainly amalgam of different half-baked components hastily thrown together to meet each new requirement and often developed by different contractors. Those who would benefit from swift implementation of the new program or requirement then start complaining to their member of Congress that the agency’s implementation is too slow.

Phase 3: Congress Castigates the Agency – and Piles on More Requirements and Oversight

The rise of the 24-hour news cycle promotes performative, viral moments heavy on style points but light on substance. This tendency reaches its apex in Congressional oversight hearings. In front of the TV cameras, many members ask thoughtful questions designed to elicit valuable information and lessons learned. However, some members focus more on simply castigating agency heads – and sometimes senior civil servants responsible for day-to-day implementation – for failing to swiftly implement new programs and priorities. Sometimes they castigate the agencies for failure at basic tasks, even when the failure is because the agency was diverted from a focus on basic, mission-critical activities by the need to scramble to meet some other new Congressional mandate.

Congress responds by passing yet more prescriptive legislation, further restricting implementers’ flexibility to adjust resources in real time as dictated by a fluid operational situation.

For example, the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1980 (PRA) intended “to minimize the burden that federal information collections impose on the public.” When it became clear that these new rules were actually creating a higher paperwork burden and disproportionately affecting small businesses – despite amendments to the law in 1986 and 1995 – Congress in 2002 attempted to solve that problem, not by revisiting the original law and rethinking whether implementation was matching original intent, but instead by passing yet another law (Small Business Paperwork Relief Act of 2002) that requires federal agencies to “publish… a list of the regulatory compliance assistance resources available to small businesses.” This additional law achieves no change to the actual burden imposed on small businesses, while creating even more requirements for agencies to produce even more text for already overstretched small businesses to wade through.

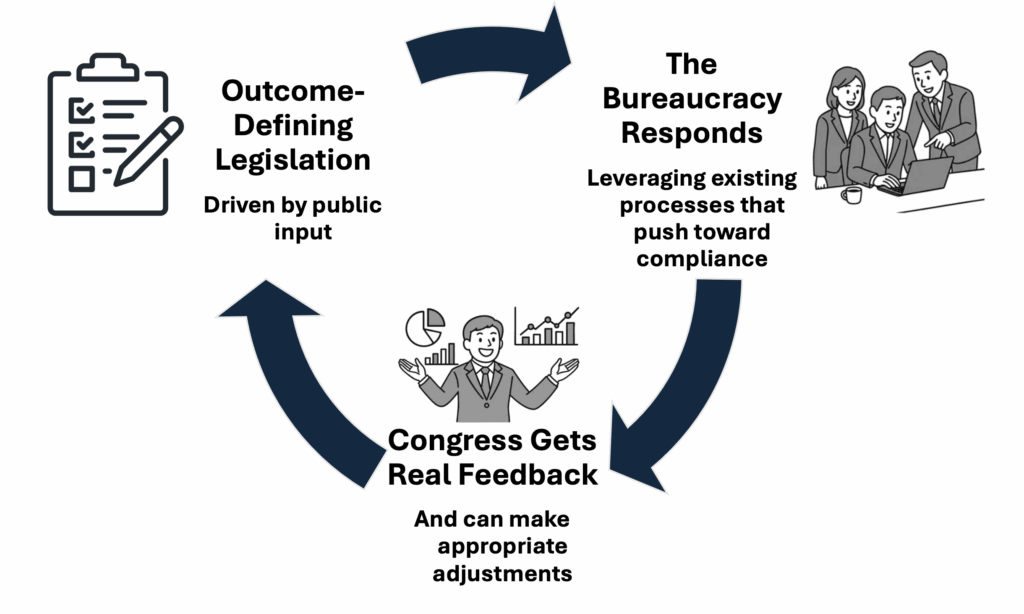

Solution: Build a Feedback Loop with Congress

In our first We the Doers workshop, participants struggled with whether we should wade into the politics of Congressional dysfunction. Ultimately, we decided that this is the crux of the problem – and just because something is hard doesn’t mean we shouldn’t address it.

However difficult it may be, we believe it is both possible and necessary to create a more productive partnership between Congress and the executive branch. We look forward to refining these recommendations as we meet with concerned voters and members of Congress.

As a starting point, we think the solutions below should be part of the conversation.

Say Less and Slow Down

Limit the length of bills, either by statute or House and Senate procedures, while increasing the amount of time members have to review and digest their contents. Either by statute or by a change in House and Senate rules, Congress could set a threshold for the amount of time a draft bill is published prior to a vote, tied to the length of the bill.

This would allow members of Congress (and their staff) to conduct meaningful consultation with their constituents, policy experts, advocacy groups, and, of course, the civil servants who would be called on to implement the bill’s provisions; better understand any tradeoffs, hidden costs, or unintended consequences; and become adequately informed prior to voting.

Ask the Doers If It’s Doable

First, focus agency legislation on the desired policy outcomes, and include fewer requirements about how federal agencies implement the bill or requirement. When drafting proposed legislation, include broad policy intent language, and a requirement for the agency to propose a concise, measurable implementation framework consistent with this intent within a reasonable prescribed timeframe. The agency would be required to present the implementation framework – as well as its analysis of any unintended impacts or hidden costs – to the relevant authorizing committee and work collaboratively with the committee to finalize an agreed-upon approach to be formalized through legislation. While this may prove challenging for more controversial programs during periods of divided government, we believe that, for most programs, this process would allow for effective coordination within the new legal reality occasioned by the Supreme Court’s decision to strike down the Chevron doctrine, which held that if Congress had not directly addressed the question at the center of a dispute, a court was required to uphold the agency’s interpretation of the statute as long as it was reasonable.

Second, create a separate mechanism for rank-and-file civil servants to raise concerns about unintended consequences of a proposed bill, hidden costs, and potential implementation challenges directly to Congressional oversight committees, without attribution or filtering by agency political staff.

While we understand and accept the need for Congressional Affairs offices staffed by political appointees fully aligned with the elected President’s vision for the executive branch, this structure has certain limitations – chiefly, that it snuffs out constructive feedback from those most familiar with the nitty-gritty operational realities. Just as the Offices of Inspector General (OIG) and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) have a means for civil servants to confidentially and anonymously submit tips, there should be a similar mechanism in Congress. This mechanism could be handled by a nonpartisan/bipartisan agency such as the Congressional Research Service.

Root Cause 3: The Budget Process Is Broken

Much ink has been spilled about Congress’s repeated failure to pass budgets on time and the disruptions this causes, and how the current administration’s use of impoundment to fail to allocate funds to programs established and funded by Congress is working its way through the courts. But less attention has been lavished on how the deterioration in the normal budget process, coupled with an explosion of complexity in government procurement and technology processes, has created the perfect storm of budgeting dysfunction.

Why It’s a Problem: Timelines, Decision-Making, and Incentives are Misaligned

Mismatch of Budget Cycle and Procurement Timelines

These days, Congress routinely fails to pass a budget by the start of the fiscal year. Under the best of circumstances, it passes a continuing resolution (CR), essentially allowing agencies and programs to operate at the same funding level as the prior year. A CR has the advantage of avoiding complete disruption – Social Security checks are still mailed, economic data is still collected and reported – but since the CR doles out funds in short-term, partial-year increments, it severely hamstrings any agency investments to fix long-festering operational issues. New IT development grinds to a halt, and hiring for key positions typically stops. Using a CR to fund the government is akin to a doctor in an ER keeping the patient on life support while waiting for a more specialized surgeon to show up and address the root cause of the malady.

The worse option, of course, is a government shutdown, where many services grind to a halt5, employees are sent home (even though they will eventually receive back pay under the Government Employee Fair Treatment Act of 2019), and the taxpayer ends up spending more money to get less due to the significant costs involved in shutting down and then restarting operations.

In either case, by the time Congress passes a real appropriation – which unlike a continuing resolution can include funds to address pressing agency needs and long-term goals, including investments in critical infrastructure and hiring to address the unfunded mandates discussed above – there is often only 9 months (or less) remaining in the fiscal year.

Why is that a problem? Because a typical government procurement official will tell you that a “full and open competition” for a new contract requires 18 months of lead time. Some of that timeline is because procurement staff are often not appropriately recruited, trained, or incentivized to expedite procurements, but much of it is because of the bewildering number of requirements contained within the now 2,000-page-long Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR). (Though we note the current administration has instructed the Office of Federal Procurement Policy (OFPP) and the FAR Council to rewrite this regulation and, presumably, reduce its length).

While there are alternatives to “full and open competition,” such as contracting to a “small and disadvantaged business” under the 8(a) program, even these alternatives take 6 months or more. And because they involve less competition – only two bids are required for an 8(a) contract – the cost may end up being higher, or the quality lower, than a procurement conducted under full and open competition.

As a result of the 9-month budget window, agencies do not have sufficient time to procure the goods and services they need through a full and open competition before the funds expire. So, agencies either use shortcuts that increase costs or fail to make the needed investment at all.

Lack of Data-Driven Decision-Making

The President’s proposed budget and Congress’ budget markups are generally based on prior-year levels, adjusted upwards or downwards by percentages aligned with administration and Congressional priorities. This is largely done for reasons of expediency, since budgets are often thrown together at the last minute with little time for members, the voting public, or advocacy groups to review and advise. As a result, many underperforming programs tend to continue receiving funds, while “superstar” programs often get only modest increases. There is little time or data available to Congress to enable informed decisions about spending.

The Process Disincentivizes Saving

When adjusting agency budgets upwards or downwards, Congress tends to penalize agencies who “fail” to spend all the money appropriated in a prior year, under the assumption that if the agency did not spend all the money appropriated, it must not have needed it.

As a result, agency heads – especially Chief Financial Officers – tend to push staff to spend as much money as possible at the end of the year. Everyone at the initial We the Doers workshop could recall examples of last-minute reminders to obligate training dollars, add money to contracts for vague additional services rendered, and generally “justify” the prior year budget by making sure all the money went out the door before the end of the fiscal year on September 30.

Prescriptive Budgets Lead to Too Much Money in One Area, Too Little in Another

Congress often appropriates large amounts of money for high-profile projects and programs that serve politically important constituencies. The large amounts sometimes are designed to signal the importance of a particular project or the fulfillment of a campaign promise; in other cases, the largesse is motivated by Congress’s sincere belief that this level of funding is needed.

However, the budget amounts are typically not reviewed by the civil servants who could more accurately forecast the funding needed.

As a result, some areas of government are overfunded and agencies have a corresponding pressure to “just spend the money” whether or not it actually generates a return for the taxpayer. Others – primarily less glamorous operational investments that could help drive results against Congress’s policy objectives – are habitually underfunded.

Solution: Fix the Budget Process

To make the budget process rational is to restore sanity and appropriate incentives to the budgeting and spending of taxpayer money.

Our recommendations in this area challenge precedent and propose admittedly ambitious changes that will affect every member of Congress and every Congressionally funded agency. We look forward to refining these as we meet with concerned voters and members of Congress.

For now, we think the following solutions should be considered:

Shut Down the Shutdowns

Avoid government shutdowns altogether by-passing legislation that automatically enacts a continuing resolution whenever Congress is unable to agree on a budget by September 30th. The government will receive its exact prior-year funding in one-month increments, unless and until a new appropriations bill is enacted.

Increase Funding Horizons

Shift all agencies from one-year to two-year funding, passing a two-year budget following the swearing in of each new Congress. This would better align the budget and procurement cycles (though it does not eliminate the need for real procurement reform), and allow Congress to allocate more time for a productive two-way dialogue with civil servants about how to improve results and federal service delivery.

To mitigate concerns that this would hamstring Congress from responding to emergencies that occur during the 2-year cycle, Congress could set aside a small portion of the 2-year budget as a contingency for emergency funding bills.

Incentivize Savings

Allow agencies to automatically retain 50 percent of unexpended funds at the end of each budget cycle for future-year use to fund agency priorities, as determined by the agency head but approved by the agency’s oversight committee. This approach would incentivize agencies to reduce wasteful year-end spending, increase funding for strategic long-term operational investments identified as high priority by those closest to the needs, and improve communication and collaboration between agencies and Congressional oversight committees.

Let Outcomes and Return on Investment Drive Operational Spending

Within federal agencies, reimagine the governance processes used to allocate appropriated funding, particularly around technology products and other long-term financial planning, to focus on attainment of citizen-focused outcome metrics (see Root Cause #1) and return on investments. This focus will incentivize and require more intensive and effective collaboration between program, IT, HR, procurement, and finance staff, and ensure agency leaders (both political and SES) are forced to make hard, intentional choices about what to prioritize and what not to prioritize. We need to stop the vicious cycle that begins with “when everything is a priority, nothing is a priority.”

Root Cause 4: Culture is Built Around Compliance, Not Delivery

Even though the members of We the Doers were part of the federal bureaucracy, the truth is we spent much of our time battling it. Some of the bureaucratic challenges we faced were externally imposed by Congress, such as the onerous six-month Paperwork Reduction Act process to change a single field on a single data collection form, but many more of them were internal to our agencies. Over and over again, a common refrain in our workshop was “we need to change the culture.”

Another common theme was the huge gulf between the official policy set forth in guidance by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) or the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), and the actual practice and implementation on the ground. Information about new flexibilities and pilots often seemed not to trickle down to agency staff or to face implementation barriers not contemplated by OMB or OPM. Much of this is driven by the fact that, just as there is inadequate feedback loop between Congress and the executive branch, there is an inadequate feedback loop between OMB and OPM and the agencies they serve.

We want to stress that we are not against compliance. We all fully complied with our responsibilities under the Constitution and the laws and regulations applicable to our agencies and programs. The problem is that there are too many requirements–many of which have unintended consequences and lack common sense–and so complying with these requirements sucks up so much time, energy, and resources, that there is little left over to ensure the agency is actually executing on its core mission and delivering results the average American can see.

Why It’s a Problem: Risk Aversion Stifles Progress

The federal government culture described by workshop participants was one of extreme risk aversion and a focus on process compliance rather than customer-focused outcomes – and it permeated all levels and functional areas of the organization.

The prevailing culture, including agency leadership, often quashes innovative ideas for service delivery because, as one participant said “the rules for yes are just too complex” or, as another said, “it’s safer to say no, because if leadership says yes and the project fails, the agency will be blamed.” And even when there is a critical mass of agency leadership ready to boldly say “yes” and embrace innovation, a single naysayer can bring change to a halt since most agency decision-making requires consensus.

This risk-averse attitude also infects the operational areas that are critical to successful program delivery, further hampering leadership’s ability to actively manage their programs even if they want to do so. Participants recounted examples of when HR staff have discouraged them from adopting skills-based hiring because it requires more administrative effort, from seeking Office of Personnel Management (OPM) approval to not hire a veteran with a history of unprofessional behavior because the process takes too long, and from removing an employee with an unsatisfactory performance record and a history of being Absent Without Leave because of fears of litigation.

In a similar vein, participants frequently struggled with procurement officials who selected the contract vehicle that was easiest for procurement but not most advantageous to the taxpayer, or who refused to hold vendors accountable despite well-documented failures to meet contract deadlines and deliverables. They recounted experiences with procurement officials asking them to make up unnecessary work for existing IT contractors whose roles had been subsumed by new in-house staff, rather than cancelling the contract, because it would be so hard to get a new contractor in the door if the in-house team failed. In another instance, procurement officials added completely redundant technical scope already known to be fully owned by in-house staff to contract renewals, because the contractor would be upset if the government started doing its own work independently.

The Behavior of People is Shaped by the Bureaucracy (not Vice Versa)

Participants went out of their way to note that most of the employees who thwarted innovation were not actively trying to make government more inefficient. They were mostly well-intentioned, hard-working folks responding rationally to the incentives and disincentives of a system that:

- punishes employees for taking actions that could result in negative publicity, end up in litigation, upset the union, result in a negative Inspector General or Government Accountability Office (GAO) audit, or ruffle the feathers of even a single member of Congress,

- holds employees accountable for compliance with policies and procedures – because that is what is easily measured – but not for moving the needle on the key performance indicators of the agency’s mission or for providing superior customer service,

- values collegiality and “relationship-building” over results, hindering the ability to have tough conversations when a fellow executive’s pet project should be de-prioritized or shelved,

- values seniority and skillful office politics over fresh new ideas that may come from the private sector or other agencies,

- prioritizes avoiding the risks of action, but doesn’t consider the risks or costs of inaction,

- is governed by statutes and regulations that in themselves are inherently risk-averse and were written to address every edge case, and

- is so complex (the Code of Federal Regulations is 190,000 pages across over 200 volumes) that no one understands all the rules – which means it is safer to “do only what has been done before.”

The Federal Hiring Process is Convoluted

Hiring processes in the federal government disempower managers and hinder their ability to hire people with the right skills, results orientation, and growth mindset.

Federal human resources (HR) hiring rules and regulations were designed with a myriad of laudable goals in mind: promote hiring for veterans, reduce bias, avoid political interference, and protect agencies from litigation. They were not, however, designed to empower hiring managers to attract, interview, and hire people with the right skills – not to mention people with the appropriate risk tolerance, appetite for innovation, or track record of overcoming obstacles to achieve results.

The participants in our workshop said a typical hiring process in their agency was complex, multistep, often siloed (with HR sometimes excluding the hiring manager from key decision points), and included significant pain points related to everything from writing accurate job descriptions to accessing candidate applications to extending to an offer for a selected candidate.

Because addressing human capital issues is so foundational to our other recommendations – and because most individuals outside government have a hard time grasping just how convoluted the process is – we think it is important to spell out the minutia of a typical federal hiring process, as we experienced it:

- The hiring manager contacts HR to request a hiring action.

- HR verifies that the hiring manager has a Billet Identification Number (BIN) authorizing them to fill that specific position on the hiring manager’s organizational chart.

- If there is no BIN number, the hiring manager cannot fill the position – even if the hiring manager has sufficient money in his or her budget to add the position, or if the hiring manager strategically decided not to fill a different position that was no longer needed.

- If the hiring manager really wishes to persist in creating a new BIN number, he or she must go through an administrative process to change his or her organizational chart. Many of these org chart adjustments require Congressional approval.

- Once HR verifies the hiring manager has authorization to hire, HR consults with the hiring manager and decides which of more than 100 hiring authorities to use.

- Hiring managers are asked, “Delegated Examining or Merit Promotion?” as if it was as simple as “Paper or plastic?” However, one requires prior federal service (merit promotion) and the other is meant for those currently in the private sector (delegated examining). Even seasoned hiring managers are often confused by the distinction, and rarely does the hiring manager know which potential applicant pool is more likely to have the highest quality applicants.

- To mitigate this risk HR will prepare paperwork to post the job multiple times under different authorities – Schedule A (disability), Pathways (students & recent graduates), merit promotion (existing government employees), military spouse, Technology Transformation Service, etc. – putting the onus on the job seeker to select and apply to the correct posting.

- If the job seeker applies to an announcement under an authority for which he or she is ineligible, he or she is disqualified even if they qualify under another authority used on a separate announcement.

- HR sends the hiring manager the position description.

- HR will typically strongly discourage the hiring manager from making any changes to the position description – even if it omits important duties or includes irrelevant ones – because any changes must go through a formal HR classification process to determine the appropriate GS level (i.e., pay band).6

- Position descriptions sometimes contain a “positive education requirement”7 that requires an applicant to possess a particular degree in order to be considered for the position – even if he or she has decades of directly relevant experience. For example, a data scientist position description will often include an educational requirement such as “Degree: Mathematics, statistics, computer science, data science or field directly related to the position. The degree must be in a major field of study (at least at the baccalaureate level) that is appropriate for the position. (Transcript must be submitted).”

- One We the Doers workshop participant recalled having to tell an exceptionally qualified data science senior manager candidate with an economics degree and an MBA, who had been a data science practitioner and data engineering leader in Fortune 100 companies for more than 20 years, that she could not hire them because the HR staffer reviewing their college transcripts could not be convinced that the candidate’s economics and business administration classes were “appropriate for the position.” The same hiring manager later had to argue the other side of this issue with HR for another candidate a web developer with a computer science degree who had zero data science experience – and spend hours explaining to multiple HR staff how not all computer-related work was identical and why this person who had never worked in data science was not actually qualified to do data science work.

- HR sends the hiring manager a list of pre-approved candidate self-assessment questions tied to the approved position description.

- This approach essentially allows candidates to self-assess whether they possess the specialized knowledge, skills, and abilities from the job description. Candidate answers are assumed to be true, regardless of whether the content of the candidate’s resume matches their assertion of relevant experience. Each potential answer to each self-assessment question is assigned a numeric score value, and HR determines aggregate score cutoffs for an applicant to be considered “qualified” or “highly qualified.” HR typically discourages the hiring manager from changing any of these questions, because any change requires a formal approval process.

- HR posts the job announcement, including the job description and the self-assessment questions on USAJobs, the portal for all federal hiring.8

- Applicants submit their resume and their self-assessment through USAJobs.

- HR provides the hiring manager with a “Certificate of Eligibles” (more commonly known as a “cert”) – a list of applicants the hiring manager is permitted to interview.

- This list consists only of applicants who rated their own skills highly enough to be considered “qualified” or “highly qualified” based on the numeric cutoffs established by HR. Qualified applicants who are honest or modest about their abilities do not make the list. If a veteran applies to a “delegated examining unit” position (i.e., a position open to members of the public and not restricted to current federal employees) and provides a self-assessment that qualifies him or her as “highly qualified” or “qualified,” the veteran vaults to the top of the list, and the hiring manager cannot interview other candidates.

- The hiring manager reviews only the resumes of candidates on the “cert” list and based on this review, invites candidates for interviews.

- Many times, the hiring manager is shocked to learn that internal candidates who clearly possess the required skill set did not make the “cert,” possibly because they were too humble when replying to the self-assessment, or because the self-assessment questions were not actually germane to the job.

- The hiring manager (usually along with a panel) conducts the interviews.

- The hiring manager is often shocked to discover that the cert-qualified candidates do not actually seem to possess anywhere near the level of qualifications they indicated in their self-assessment. Many participants in our workshop recounted interviewing “highly qualified” candidates that could not even understand the questions posed to them and weren’t aware of basic job-related terms.

- If a veteran was rated “qualified” or “highly qualified” but, after interviewing, the hiring manager does not believe he or she is a good fit for the role, HR typically advises the hiring manager to either hire the veteran anyway or to cancel the hiring action and start all over. If the hiring manager persists, HR may advise the hiring manager to submit a waiver from veterans’ preference requirements to the Office of Personnel Management. But HR typically discourages this as it requires additional time, energy, and paperwork in a process that can drag on for several months. If the hiring manager is eventually permitted to consider non-veteran candidates but none of these candidates appears to be a good fit, the hiring manager is not permitted to go back and look at the candidates who did not meet the “qualified” cutoff. Instead, he or she must start all over with a new job posting.

The result of this complex process is that many hiring processes end without anyone hired and, even when an agency is successful in hiring someone off the “cert,” the process outlined above typically takes 3-6 months and may result in only a mediocre hire. Potentially better candidates never even make it on the “cert” list, either because they are not veterans (and another candidate is), they do not meet a positive education requirement, they are not eligible to be hired under the particular hiring authority selected, or they are too humble (or honest) when completing the self-assessment – despite having superior skills to those who lie about their qualifications and are therefore rated as more qualified.

OPM has created some flexibilities that ease some of these issues, but HR staff generally remain unfamiliar with these flexibilities and are hesitant to use them. One workshop participant was successful in creating a skills-based “case study” method for hiring, which required applicants rated “qualified” or above in the self-assessment stage to complete a practical exercise that mirrored the actual work of the team. While this did improve the quality of hires, it still did not eliminate the inherent issues with the self-assessment (HR refused to remove the initial step, even though this step is not required by law or regulation), and it required approval from three levels of HR management and reams of paperwork, adding about 8 weeks to the hiring process.

Many agencies have availed themselves of Direct Hire Authority, which sidesteps some portions of process outlined above for hard-to-fill positions. This approach allows hiring managers to view all applicant resumes (no “cert” screening step is required) and waiving veterans’ preference rules. However, hiring managers frequently get stuck on procedural constraints like positive education requirements and HR team confusion about or disagreement with the modified rules for selection, offer, and onboarding of Direct Hire candidates.

Some agencies have also adopted “shared certs,” allowing their hiring managers to interview candidates on other agencies’ certs, if the cert is for the same type of position (e.g., “Civil Engineer”). However, many agencies have HR staff who are not aware of this option, do not have updated policies allowing them to leverage this option, or have overly restrictive internal requirements preventing them from using the shared certs. To use a shared cert, the job series, pay level (GS), and job location must all exactly match the recruitment position. Using a shared cert also means that a hire can be made without publicly posting the position, which can conflict with other transparency and fairness practices.

Performance Management Has Been Replaced by Litigation Avoidance

The merit protection system was designed to ensure the civil service remained professional and nonpartisan – rather than stuffed with a president’s unqualified political cronies through the “spoils system” that existed prior to the 1880s – and to ensure that employees had appropriate due process when threatened with a disciplinary action or removal from federal service.

We are firmly committed to the principle of a nonpartisan civil service of subject matter experts, and to the principle of due process. However, as former managers in the civil service, we have seen firsthand that, at least prior to 2025, the pendulum had swung too far towards protecting underperforming employees.

While a formal system existed for removing employees through the Merit Systems Protection Board, the process was lengthy – typically two years or more – and involved hundreds of hours of the manager’s time documenting the employee’s failure to complete assigned tasks, placing the employee on a “demonstration opportunity” (which often goes through three or more rounds of HR review), dealing with the employee’s often (though not always) spurious discrimination and disability claims, participating in (nearly always unsuccessful) mediation with the employee, and then handling the employee’s appeals to the Merit System Protection Board.

At every turn, the manager was discouraged from taking action by an army of lawyers, HR specialists, EEO specialists, and union representatives. And, if that were not enough to discourage most managers, managers have the added threat that the employee would file a claim directly against them. The agency will then spend resources investigating the manager, and the manager will have to spend time responding to this investigation – and sometimes even need to spend his or her own funds to hire outside counsel.

In 2025, of course, the pendulum swung the other way, with many employees fired simply for being in their probationary year of service, without a shred of documentation that the employee failed to meet performance standards. This complete disregard for due process and the quality of the employee skips the hard work of reforming the performance management systems, and demonstrates to employees that the quality of their work doesn’t matter. This approach cannot be the long-term solution to federal employee management.

Oversight Bodies Emphasize Compliance More Than Results

Federal program managers learn to live in fear of audits by the Office of Inspector General (OIG) and the Government Accountability Office (GAO), as well as hearings by Congressional oversight committees. GAO reports often include substantive and helpful assessments of individual program’s success in meeting specific Congressional objectives but typically do not focus on the overall effectiveness of agencies in meeting their mission. Inspectors General focus on identifying fraud, waste, or abuse, and on determining whether agencies and programs are complying with pertinent statutes and regulations. And Congressional oversight committees often focus on agencies’ progress in addressing GAO or OIG audit findings, or on negative media publicity. This multi-faceted focus on compliance instead of results further incentivizes the government’s risk-averse, compliance-oriented culture.

Oversight entities rarely point out when an agency is doing anything right. In fact, one workshop participant noted that her agency’s OIG refused to publish its audit of her program because the OIG could not find any instances of noncompliance. The OIG was not incentivized to publish a report with no findings, so they did not do so. But in the process, they deprived the agency of good publicity and deprived the federal government of an example of what to do instead of what not to do.

Government is a Gullible Customer

Human capital development, accountability frameworks, and customer feedback and continuous improvement loops are sorely neglected in support functions.

Federal workforce support roles – procurement officers, contracting officers, contracting officers’ representatives, and IT – as well as program staff generally lack the knowledge, skills, and capacity to effectively identify business requirements for federal contracts, accurately estimate and budget for full lifecycle costs, evaluate contractors’ expertise and value, oversee and evaluate contractor performance, and hold underperforming contractors responsible.

As a result, contracts are often written based on the vendor’s suggestions, through the lens of their financial self-interest.

This problem is most evident in government technology contracts, where federal “IT” staff often have limited hands-on technology development experience and therefore little sense of what is required to achieve technical delivery.

Leadership Doesn’t Lead

The federal officials who participated in our workshop were all in leadership roles and told stories of making bold choices to focus on the mission despite the constraints. But the reality is that these leadership decisions were irrational and unusual within the current government culture – exposing us to higher levels of professional risk than most leaders are willing to take, and requiring us to expend inordinate amounts of time and energy fighting the bureaucracy instead of focusing on higher-value activities

Most agency senior executives are more than two decades into their government careers when they are promoted to their capstone roles and have seen firsthand that it is a safer career option to focus on following the rules and “doing what’s been done,” rather than pushing colleagues to make the hard choices necessary to produce better outcomes for American citizens and taxpayers.

We identified the following root causes for this phenomenon:

- The pre-2025 recruitment and selection process for members of the Senior Executive Service (SES) was overly reliant on candidates’ essays demonstrating the Executive Core Qualifications (ECQs) – essentially, a self-assessment process that has spurred an army of consultants and even an Office of Personnel Management class to assist candidates in writing – and on formal candidate development programs run by individual agencies, which tend to select civil servants who have “paid their dues” over a long tenure and avoided rocking the boat too much. We do want to acknowledge that the process has very recently changed, and it is too soon to determine the effect of the quality of SES hires. This new process replaces the ECQ essays with a 2-page resume that must demonstrate the five new ECQs which include “driving efficiency” (which we welcome) and “Commitment to the Rule of Law and the Principles of the American Founding” (which we are concerned could be an attempt to politicize the SES). It also prioritizes “validated executive assessments such as work simulations, reasoning assessments, accomplishment records, and/or situational judgment tests” and requires the majority of selection panel members to be political appointees.

- Some SES become entrenched in their positions and too powerful in internal organizational politics to challenge, even when that official is making decisions that – in the opinion of his or her subordinates or peers – are detrimental to the agency mission or cost-effectiveness.

- In some agencies the only requirement for becoming the leader of a program area is general management expertise. It is not necessary for the Chief Technology Officer to have written a line of code. It is not necessary for a Chief Customer Experience Officer to have worked on the front lines with customers. The list goes on. If leaders don’t know how to do the frontline-level work, they naturally defer down the chain for decision-making and effectively abdicate the responsibility of their roles.

- In other agencies, those employees with deep subject matter expertise but little track record of successfully managing projects and teams are elevated into the SES, with suboptimal results.

- SES performance plans are often filled with boilerplate compliance requirements and adherence to executive orders, not moving the needle on the types of meaningful metrics we describe above. For example, one workshop participant described how her 2024 performance plan held her accountable for the number of contracts to small and disadvantaged businesses, but not whether the contracts produced cost savings or whether the contracted-out projects were delivered on time and on budget.

- An excessive number of political appointees can act as a drag on operational performance. We have certainly worked with many talented and hard-working political appointees. However, we have worked with some whose primary qualifications seem to be that they were an excellent campaign fundraiser or successfully ran a private-sector business, which does not mean they are capable of effectively running a large and complex federal agency. In addition, the nature of an appointment with a political mandate requires most appointees to come into an agency with a specific agenda. As a result, many political appointees focus almost exclusively on enacting one of the administration’s policy priorities, to the detriment of turbocharging efficiency or performance. Few, if any, have the time, inclination, or institutional knowledge to effectively tackle the constraints we list in this report.

Technology Is Dramatically Misunderstood

For decades, the federal government has been funding projects aimed at technology “modernization.” This concept is inherently flawed. There is no such thing as a modernization effort, because as soon as the technology project to bring a given product or system up to a contemporary standard is complete, the goalpost shifts and the state of the industry evolves. Technology products are never “done,” and “modernized” is a claim that is false the moment it is uttered.

Technology is also not a standalone part of an agency’s work. Technology is the foundation on which all government services are built. The vast majority of agency interactions with the public are through digital products. The large-scale systems used to meet physical public needs (e.g. transportation infrastructure, emergency aid distribution, etc.) require robust technical and data platforms to function. Even the way the government communicates both within itself and to the public requires significant technical infrastructure. Therefore, the design, construction, management, ownership and evolution of technology systems cannot be left to a siloed group of “IT experts.”

Government leaders no longer have the luxury of choosing not to engage with “technical details,” data dictionaries, product roadmaps, or other foundational artifacts of technical product management. These are the artifacts of a functional government in 2026.

Technology Products are Built the Wrong Way

Government technology products are almost never intentionally designed.

Long-term visions and roadmaps for both citizen-facing and internal products are exceedingly rare, because – largely due to the bottom line and budget issues described earlier in this document – technology has historically been “purchased” as if it were a commodity that one can buy and put in place and then ignore. The accumulation of commodity-style purchases has produced technical systems that are patchwork quilts of quick fixes and political priorities. These patchworks are often layered on top of brittle, basic frameworks quietly built by small groups of frontline engineers totally disconnected from the agency’s vision or mission, with no context for the goals of the product they are building or how it might need to scale.

Even in the largest federal agencies, like the Internal Revenue Service with more than 8,000 employees in IT positions, almost nothing is built by in-house teams. Instead, the government outsources its mission-critical tax administration systems to third parties with a vested interest in making the government dependent on them – and in making the system as complex and expensive as possible. We outsource core, mission-critical functions like taxpayer record-keeping and authentication of end users by funding contractor-defined projects that are comprised of arbitrary feature lists developed years in advance. We intentionally remove any opportunities to build iteratively and responsively, because vendors are required to deliver the specific features defined in their contract regardless of changes in customer expectations, user research results that suggest adjustments, or sea changes in the state of the industry.

Occasionally, the government has built game-changing, high-quality technical products using normal private sector methodologies and federal staff. For example, one of our workshop participants has successfully launched three customer-facing IT systems on time and on budget – sometimes in as little as four months – by working with procurement staff to leverage existing blanket purchase agreements (BPAs) with pre-vetted contractors on a standard off-the-shelf platform (Salesforce), leading program staff in developing very detailed business requirements, developing her own test scripts and detailed in-house software testing of real data inputs (rather than outsourcing this to the vendor), and working with the vendor to implement a true agile process with a new release every three weeks. This flexible, iterative approach allowed her tiny team to be the first federal program to add a feature to allow for electronic submission and processing of Build America, Buy America waivers.